Polícia Federal, Rodoviária Federal e Civil do Distrito Federal, a exemplo do FBI americano, cometem discriminação ao se utilizarem de subterfúgios e argumentação falaciosas para barrar o acesso legítimo de deficientes em seus quadros

O artigo abaixo (em inglês), de autoria de McGowan, bem como os seus anexos, relatam, em suma, a decisão do judiciário americano, que determinou que o FBI (a Polícia Federal dos Estados Unidos) garantisse o cargo/emprego ao agente especial, proveniente das forças armadas, que ficou cego de um olho (monocular).

Após ser indicado/recomendado ao posto no FBI, ao ser submetido a alguns exames, foi caracterizado a deficiência do agente, o que fez com que a polícia americana, por discriminação (segundo a sentença), retirasse a oferta, alegando uma série de ‘restrições’ estapafúrdias. O caso foi parar no judiciário, através do chamado EEOC (uma espécie de Ministério Público americano especializado na defesa dos deficientes e inserção destes na sociedade), que reverteu a decisão na justiça e manteve o agente na ativa.

Guardadas as devidas proporções, algo muito parecido está ocorrendo atualmente, de forma velada, com as polícia Federal e Rodoviária Federal tupiniquim (e igualmente com a Polícia Civil do Distrito Federal), nos concursos em andamento, ou seja, estão ‘fabricando’, em que pese a farta legislação vigente que protege esta parcela da população, vários argumentos falaciosos para impedir o prosseguimento dos deficientes (mesmo estes tendo sido aprovados, em igualdade de condições) nas demais etapas do concurso para os cargos de delegado, escrivão e perito, para a PF e de policial rodoviário, para a PRF.

Todos estes candidatos que foram ‘discriminados’ (não consigo encontrar outra palavra) por estas corporações, estão recorrendo ao judiciário e conseguindo liminares para que continuem nas demais fases, incluindo o curso de formação, e posteriormente tomem posse nos respectivos cargos.

Outro fato, no mínimo curioso, está acontecendo também, neste exato momento no Distrito Federal, onde a Polícia Civil (talvez ‘inspirada’ pela PF e PRF), através do CESPE/UnB (Centro de Seleção e de Promoção de Eventos), é responsável pela condução de dois concursos para o provimento de vagas para os cargos de escrivão e agente, e, infelizmente também adotou a infeliz ou ‘eugênica’ saída para barrar a entrada dos candidatos PNEs (portadores de necessidades especiais) em seus quadros, alegando igualmente, a incompatibilidade para o exercício das funções de policial (mesmo a legislação determinando e diferentemente do espírito da decisão da Ministra Carmém Lucia, que esta pretensa incompatibilidade só pode ser declarada ao final do estágio probatório e não pela ‘banca’, por uma canetada).

O interessante e ao mesmo tempo vergonhoso para a PCDF (e para o CESPE) é que esqueceram que a corporação já possui em seus quadros inúmeros delegados, papiloscopistas, escrivães, agentes e peritos que são deficientes e foram aprovados no último concurso (conduzido pela Fundação Universa) e estão, de forma competente e sem nenhuma ocorrência que os desqualifiquem, desempenhando, em igualdade de condições, as funções para as quais foram aprovados e tomaram posse.

Algumas perguntas que caberiam ao CESPE e a alta direção da PCDF: Por que desta mudança de entendimento/postura em relação ao último concurso, sendo que a legislação permanece a mesma? Existe algum direcionamento ou determinação para se barrar o acesso dos PNEs nos quadros da PCDF? Os policiais PNEs da ativa também são inaptos para o exercício das funções? O que mudou?

Por: Marcos Paulo Batista de Oliveira

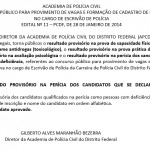

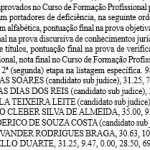

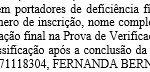

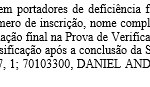

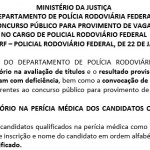

Abaixo constam extratos de publicações do Diário Oficial do Distrito Federal onde se evidencia a existência de candidatos que se declararam serem portadores de deficiência física e que foram aprovados nos últimos concursos promovidos pela Polícia Civil do Distrito Federal e conduzidos pela Fundação Universa. Constam também os editais divulgados pelo CESPE, referentes aos concursos em andamento da PF, PRF e PCDF, que atestam e afrontam a legislação vigente e a tendência mundial de inserção dos PNEs em todas as atividades laborais, desde que, em igualdade de condições, sejam aprovados em todas as fases dos respectivos certames:

- Escrivão – PCDF

- Exemplo de liminar concedida

- Delegados – DODF, de 1/12/10, pg. 49

- Escrivães – DODF, de 30/01/09, pg. 85

- Papiloscopistas – DODF, de 30/01/09, pg. 84

- Peritos – DODF, de 30/01/09, pg. 87

- Escrivães – Polícia Federal

- Delegados – Polícia Federal

- Peritos – Polícia Federal

- Policial Rodoviário Federal – PRF

Texto e anexos referentes ao caso do FBI americano:

FBI Must Revive Special Agent Job Offer To Applicant Blind in One Eye – EEOC – Equal Employment Opportunity Commission

By Kevin P. McGowan

The Justice Department must revive a conditional offer of employment as an FBI special agent to a former Army captain who essentially lacks vision in his right eye, because DOJ violated the Rehabilitation Act by deeming the applicant a “direct threat” to safety without conducting an adequate individualized assessment, a divided Equal Employment Opportunity Commission decided July 19 (Nathan v. Holder, EEOC).

Affirming an EEOC administrative judge’s 2006 order that DOJ unlawfully discriminated against applicant Jeremy Nathan, EEOC said Nathan was a qualified individual with a disability under the Rehabilitation Act and DOJ did not meet its burden of showing Nathan’s monocular vision posed a direct threat to the safety of himself or others.

EEOC Chair Jacqueline Berrien and Commissioners Chai Feldblum and Jenny Yang approved the opinion drafted by EEOC’s Office of Federal Operations and signed by Bernadette Wilson, EEOC’s acting executive officer.

EEOC Commissioners Victoria Lipnic and Constance Barker, the commission’s two Republicans, voted against approval.

Dissent Sees Troubling Implications

In her written dissent, Barker objected that EEOC skimmed over the question of whether Nathan, who has an artificial lens and 20/800 vision in his right eye, was “qualified” to perform the essential functions of an FBI special agent.

The FBI properly questioned Nathan’s ability safely to “clear a room,” given Nathan’s visual impairment, Barker wrote, as Nathan admitted he has limited peripheral vision and a permanent blind spot that cannot be completely eliminated by Nathan’s techniques to compensate for his impairment.

The dissent called EEOC’s decision “particularly disturbing” because of its implications for other federal, state, and local law enforcement agencies.

“It is common knowledge that all federal law enforcement agencies, including the Secret Service, the Marshals Service (which protects federal courthouses and the flying public), and Customs and Border Patrol, have vision standards,” Barker noted. “This decision appears to effectively raise the requirements for individualized assessments conducted to establish direct threat. There is no reason this new heightened requirement would not apply to all law enforcement agencies–not only federal law enforcement, but also state and local law enforcement agencies.”

Eye Surgeries Did Not Correct Vision

Nathan is a U.S. Military Academy graduate who served as an infantry officer, was honorably discharged in 1998, and has a law degree and a masters’ degree in business administration, EEOC recounted.

Beginning in 1993, however, Nathan noticed a change in his eyesight and eventually was diagnosed with a detached retina. In 1997, doctors performed a series of surgeries on his right eye. Although the surgeries were ineffective in improving Nathan’s vision, they stopped the progression of damage to the eye, EEOC said. After Nathan developed a cataract in response to the surgeries, doctors placed an artificial lens in his right eye.

The result is Nathan has 20/800 vision in his right eye, limited peripheral vision, and his “field of vision” permanently includes a blind spot, EEOC said.

In 2002, Nathan applied for an FBI special agent position and the agency extended a conditional job offer. But after a required medical exam, the FBI withdrew the job offer after its chief medical officer advised that Nathan’s “substandard vision” was “unacceptable for safe and efficient job performance.”

Nathan filed a discrimination complaint under the Rehabilitation Act. Following a two-day hearing, an EEOC administrative judge (AJ) in September 2006 ruled the FBI had violated the act by discriminating against Nathan based on his disability. The FBI asked EEOC to reverse the AJ’s decision and affirm an FBI final agency order rejecting Nathan’s discrimination claim.

‘Disability’ Under Pre-Amendment Law, EEOC Says

Disability discrimination claims under the Rehabilitation Act are subject to the same analysis as those under the Americans with Disabilities Act. The FBI contended that under the law as it existed in 2002, prior to the ADA Amendments Act, Nathan was not an individual with a disability and the FBI did not regard him as a disabled individual.

The FBI further argued Nathan was not a “qualified individual with a disability” because his eye impairment prevented him from meeting special agent job qualification standards that are job-related and consistent with business necessity. The FBI contended it also proved Nathan would pose a “direct threat” to the safety of himself and others if he were hired as a special agent.

The AJ did not err in finding Nathan was a qualified individual with a disability, EEOC said. Nathan met all the FBI’s job requirements except the vision standard and was extended a conditional job offer “that reflected his achievement,” EEOC said. The FBI’s medical report described Nathan as in overall good health, noting only his vision impairment, EEOC said.

“The key question then is whether the vision standard that [Nathan] failed, or the manner in which [the FBI] applied the vision standard to [Nathan], is consistent with the requirements of the Rehabilitation Act,” EEOC said. “If the standard itself fails to meet the ‘job-related and consistent with business necessity’ requirement, or if [the FBI] failed to apply the standard in an appropriate way (for example, by failing to determine whether performance could be achieved through reasonable accommodation), [Nathan] has a valid claim.”

Failure to Perform ‘Individualized Assessment.’

The FBI requires special agents to have uncorrected vision of 20/200 in each eye, with correction to 20/20 in one eye and 20/40 in the other eye. Nathan’s conditional job offer was withdrawn because the FBI’s chief medical officer found his limited vision created a “risk of substantial harm to the health or safety of the applicant and co-workers while working in critical response tasks of raids, arrests, and reactive squad duty.”

Under relevant EEOC regulations, a person with a disability can be a “direct threat” if he poses a “significant risk” to the health or safety of himself or others that “cannot be eliminated or reduced to an acceptable level” by reasonable accommodation, EEOC said. Whether an individual poses a direct threat must be based on “an individualized assessment of the individual’s present ability to perform the essential functions of the job,” EEOC said. “If no such accommodation exists, the agency may refuse to hire the applicant.”

Substantial evidence supports the AJ’s conclusion the FBI did not perform an individualized assessment of whether Nathan could safely perform the essential functions of the special agent job, EEOC decided.

The FBI “relied heavily” on testimony from the manager of the FBI academy’s safety and survival training program to show Nathan posed a direct threat, EEOC noted. That witness testified that individuals with reduced peripheral vision and depth perception present a significantly increased safety risk in situations when a special agent must “clear a room,” that is, enter and secure a confined space where dangerous persons might be present.

The FBI program manager cited an FBI study which found that a person with one eye blocked lost approximately 35 to 38 percent of their field of vision and would be unable to see approximately a five-foot area while clearing a room.

But EEOC said the FBI study alone was insufficient to establish a “high probability of substantial harm” to Nathan or others if he were hired as a special agent.

“The evaluation of an individual’s unique abilities and disabilities is the crux of an individualized assessment,” EEOC said. “At the minimum, such an assessment should take into account any special qualifications that might allow an applicant to successfully perform the essential functions of a position without posing a direct threat to himself or others. Examples of special qualifications include prior successful experience in a similar position and adaptive or learned behaviors that compensate for physical limitations imposed by a condition.”

‘Special Qualifications’ Must be Considered

The FBI study, which considered the range of vision lost by a typical person with monocular vision, “plainly failed to examine any of the special qualifications” Nathan allegedly possesses, EEOC said. The FBI “summarily disqualified” Nathan based on a “presumption that no individual with monocular vision can carry out” a special agent’s duties, EEOC said.

An appropriate individualized assessment “would have closely evaluated” Nathan’s prior experience to determine if it indicated an ability to safely perform as a special agent, EEOC said. If past experience was insufficient, the FBI should have provided Nathan with “an opportunity to demonstrate how he can safely perform” the job “because of compensatory skills he has developed,” EEOC said.

Nathan’s experience as an infantry officer leading combat patrols in Bosnia predated his unsuccessful eye surgeries and is “not probative evidence” of Nathan’s present ability, EEOC said.

EEOC said “more relevant” to the analysis are the “special skills” that would enable Nathan to perform the essential functions of the special agent job safely.

“These include learned behaviors, including skills obtained prior to surgery, and compensatory techniques that assist [Nathan] in overcoming his vision impairment and enable him to perform such essential functions as clearing a room,” EEOC said. “There is no evidence in the record [the FBI] took these skills into account when assessing whether [Nathan] could safely perform the essential functions of a [special agent]. An appropriate individualized assessment would have allowed [Nathan] to demonstrate how those special skills enable him to perform the essential functions of the job without significant risk to himself or others.”

Given Nathan’s visual impairment, the FBI “had a legitimate concern” regarding his ability to perform the job, EEOC said. But the AJ correctly found the FBI did not meet its burden to show “direct threat” under the Rehabilitation Act, EEOC ruled.

EEOC ordered the FBI to reinstate Nathan’s conditional job offer, commence its background investigation of Nathan, and notify Nathan of upcoming new agent training classes. If Nathan passes the background check, the FBI should determine the appropriate amount of back pay and benefits calculated from the date of the first training class that began after Dec. 5, 2002, the date the FBI revoked the conditional job offer, EEOC said.

Dissent Would Find Sufficient Assessment

The dissent “strongly disagree[s]” that the FBI failed to conduct an individualized assessment, Barker wrote.

The FBI conducted “a detailed simulation” to test the range of vision of a person with monocular vision in a “clear the room” situation and concluded there would be approximately a five-foot area the person could not see, the dissent emphasized.

“The FBI did not simply decide that monocular vision was incompatible with safely performing key essential functions of a special agent but actually created a simulation of a dangerous situation to determine precisely what the impact would be in the field of vision,” Barker wrote.

Barker said she is not suggesting “employers may always, or solely, rely on general studies” to prove direct threat. “But where, as here, the limitations of the disability do not change, then a study such as the one conducted by the FBI can produce highly relevant evidence that an applicant poses a direct threat,” she wrote.

EEOC fails to “point to any special qualifications” Nathan possessed that would negate the FBI’s direct threat finding, the dissent said. Nathan conceded he has a permanent blind spot and that turning his head to compensate for limited peripheral vision “moves the direction of that blind spot but does not eliminate it,” Barker wrote.

EEOC “fails to specify even one prior activity in Nathan’s job history that would eliminate or even lessen the significant risk of substantial harm in clearing a room caused by his permanent visual limitations,” the dissent said.

EEOC’s decision seems to rest on the FBI’s failure to permit Nathan to demonstrate whether he poses a direct threat, the dissent noted. But “there is nothing in the [Rehabilitation Act and ADA] or [EEOC] regulations that require an employer to set up a simulation involving an applicant to show the existence of a direct threat, and the absence of such a demonstration does not constitute a failure to do an individualized assessment,” Barker wrote.

Applicant Not ‘Qualified,’ Dissent Says

EEOC also failed to show how Nathan was qualified for the job, the dissent said. “Remarkably, despite the lack of this required finding [EEOC] orders the FBI to treat Nathan as if he had been found to be qualified, and to reinstate its job offer and admit him to its next new agent training classes,” Barker wrote. “However, such remedies would only be available if [EEOC] had found that Nathan is qualified–something this decision conspicuously fails to do.”

“It is deeply regrettable that Nathan, with his history of service to this country, has developed vision problems that prohibit him from serving as an FBI special agent, but the fact remains that the law provides that if an applicant is unable to perform even one of the essential functions of a job he is not a qualified individual with a disability under the law,” the dissent said.

The FBI, after an individualized assessment, determined Nathan could not perform the essential function of “clearing a room,” the dissent said.

“It is important that we not forget that this is not the typical work environment we are discussing here,” Barker wrote. “We are talking about life threatening situations where a delayed response of mere seconds could mean death. I believe the facts clearly demonstrate that Nathan was unqualified. Thus, the FBI had no obligation to reinstate his offer of employment.”

Text of EEOC’s decision is available at nathaneeoc.pdf and text of Barker’s dissent is available at nathandissent.pdf.