Texto muito interessante, recomendado pelo professor Lobão, de Direito Penal, onde a revista inglesa ‘The Economist’, em reportagem sobre as prisões da America Latina, faz um ‘raio x’ da situação atual e as perspectivas com relação ao nosso ‘sistema de reabilitação e ressocialização carcerário’ (ou seria faculdade do crime?). Este assunto está sendo tratado na cadeira de Direito Penal. Vale a pena a leitura!

Far from being secure places of rehabilitation, too many of the region’s jails are violent incubators of crime. But there are some signs of change

ON AUGUST 28th six members of the local Human Rights Council, an official watchdog, turned up at Romeu Gonçalves de Abrantes prison in João Pessoa, the capital of the state of Paraíba in Brazil’s poor north-east. Inside they found filthy, overcrowded cells holding sick, thirsty prisoners, some with untreated injuries. The prison guards refused to open the door of the locked punishment wing, which reeked of vomit and faeces. So the visitors passed a camera in through a ventilation shaft. It came back with images of naked prisoners crowded into bare, unlit cells. Though the guards said the inmates were being held like this “temporarily” because of a planned jailbreak, they had been there for four days. The guards demanded the camera be handed over. When the council members refused, all six were detained. They were held for three hours before other state officials turned up and freed them.

ON AUGUST 28th six members of the local Human Rights Council, an official watchdog, turned up at Romeu Gonçalves de Abrantes prison in João Pessoa, the capital of the state of Paraíba in Brazil’s poor north-east. Inside they found filthy, overcrowded cells holding sick, thirsty prisoners, some with untreated injuries. The prison guards refused to open the door of the locked punishment wing, which reeked of vomit and faeces. So the visitors passed a camera in through a ventilation shaft. It came back with images of naked prisoners crowded into bare, unlit cells. Though the guards said the inmates were being held like this “temporarily” because of a planned jailbreak, they had been there for four days. The guards demanded the camera be handed over. When the council members refused, all six were detained. They were held for three hours before other state officials turned up and freed them.

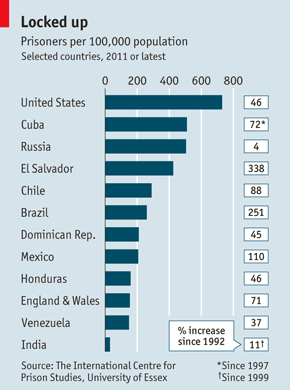

Such conditions are closer to the rule than the exception in Latin America’s jails. Compared with other parts of the world, the region locks up a larger—and rising—percentage of its population, though less than the United States (see chart). But few Latin American prisons fulfil their basic functions of punishing and rehabilitating criminals. Not only are prisoners frequently subjected to brutal treatment in conditions of mass overcrowding and extraordinary squalor, but many jails are also themselves run by criminal gangs.

Such conditions are closer to the rule than the exception in Latin America’s jails. Compared with other parts of the world, the region locks up a larger—and rising—percentage of its population, though less than the United States (see chart). But few Latin American prisons fulfil their basic functions of punishing and rehabilitating criminals. Not only are prisoners frequently subjected to brutal treatment in conditions of mass overcrowding and extraordinary squalor, but many jails are also themselves run by criminal gangs.

One result has been a recent rash of prison massacres and fires, some set deliberately. In Honduras a fire killed more than 350 inmates at a jail in the central town of Comayagua in February. In the same month in Mexico three dozen imprisoned members of the Zetas, a drug gang, murdered 44 other inmates at a jail at Apodaca, near Monterrey, before escaping. Last month at least 26 prisoners died in a battle between gangs inside Yare jail in Venezuela. The authorities later seized a small arsenal from prisoners, including assault rifles, sniper rifles, a machine-gun, hand-grenades and two mortars. A similar number died in a riot at El Rodeo, another Venezuelan prison, last year, which saw gang bosses hold out against thousands of national-guard troops for almost a month.

A fire begun during a fight between inmates at San Miguel prison in Santiago, Chile’s capital, in December 2010 killed 81 prisoners and injured 15. Survivors said a group of inmates used a homemade flame-thrower, fashioned from a hosepipe and a gas canister, to set fire to a mattress barricade erected by a rival group in their barred cell. San Miguel was not a high-security jail, and the victims of the worst prison fire in Chile’s history were all serving sentences of five years or less, for crimes such as pirating DVDs and burglary.

Just as deadly, though less headline-grabbing, is the quotidian tragedy of prison killings in the region. In Venezuela under President Hugo Chávez, a socialist, more than 400 prisoners were killed each year between 2004 and 2008; by last year, the figure had risen to 560, and it looks set to top 600 (out of a prison population of around 45,000) in 2012, according to the Prisons’ Observatory, an unofficial watchdog. In other words, a Venezuelan is at least 20 times more likely to be murdered in jail than on the streets, despite a steep climb in the country’s overall murder rate over the past decade. Even prison governors are not immune: two have been murdered this year. In Mexico prison deaths have risen in tandem with the expansion of organised crime, from 15 in 2007 to 71 in 2011 and more than 80 in the first three months of this year, according to Eduardo Guerrero, a security expert.

Gangland penitentiaries

The main reason for the violence is that many jails are in practice run by gangs, which use them as refuges where they can organise further crimes on the outside. Many deaths result from clashes between rival gangs over the lucrative businesses of extorting money out of fellow inmates and trafficking drugs and weapons into jail. A prisoner pays for everything inside, including a place to sleep and even the right to live. In El Salvador’s jails mobile-phone SIM cards change hands for around $250, says Miguel Ángel Rogel Montenegro, a human-rights activist.

In Venezuela the only functions performed by prison guards are perimeter security, a daily headcount and the transfer of prisoners to court. Whereas relatives are submitted to humiliating strip searches at visiting time, it is no secret that the guns, drugs, mobile phones and other items that are available on the inside are trafficked by the national guard, which is responsible for perimeter security.

In Mexico prisoners do what they please in some jails run by local governments. Last year police raided a prison in Acapulco to find 100 fighting roosters, 19 prostitutes and two peacocks on the premises. A few months earlier prisoners in a Sonora jail were found to be running a raffle for a luxury cell that they had equipped with air conditioning and a DVD player. In 2010 it emerged that guards at a jail in Durango had allowed prisoners out at night to commit contract killings.

Jail breaks have become increasingly common in Mexico. On September 17th more than 130 inmates used a tunnel to flee a prison at Piedras Negras, close to the border with the United States. Earlier this month a gang leader vanished from Tocorón jail in Venezuela; in all, up to 100 of the country’s prisoners may have escaped in recent months.

A quirk in Brazil is that the origin of the country’s most powerful gang, the Primeiro Comando da Capital (PCC), lies inside the prison system. The PCC was founded at Taubaté jail in São Paulo state in 1993, to fight for prisoners’ rights and avenge the massacre by police of more than 100 prisoners at Carandiru, another jail, the previous year. Since then, the PCC has moved beyond prison walls into extortion, drug-running, prostitution and murder. In 2006 it brought São Paulo to a standstill after the government ordered a crackdown on its leaders. Kingpins behind bars co-ordinated riots in 73 of the state’s 144 prisons while also ordering bank robberies and the torching of buses in mayhem that saw scores of people killed, most of them by the police.

The PCC now controls most of São Paulo’s prisons (other states have prison gangs as well). It has a policy of non-communication with guards, whom it calls “Germans” (meaning Nazis). Marcos Fuchs, a lawyer at Conectas, a human-rights group in São Paulo, who has been visiting prisons since 2004 says that he does not speak to inmates without a gang boss listening in. To do otherwise risks retribution, in the form of what in prison argot is called “Gatorade” (cocaine, Viagra and water) poured down a prisoner’s throat at night, in quantities large enough to induce cardiac arrest.

After gang control, the second systemic failing of Latin American jails is overcrowding and thus inhuman conditions. Brazil’s prisons, for example, held 515,000 inmates last year—the world’s fourth-largest prison population, behind the United States, China and Russia—and around two-thirds more than its prisons were built for. In 1990 there were just 90,000 prisoners. Mr Fuchs has seen cells built for eight men holding 48, cases of gangrene and tuberculosis left untreated and prisoners kept in unventilated metal shipping containers under the baking sun. The report of a congressional inquiry into prison conditions, published in 2009, documented routine beatings and torture by guards, filthy and inadequate food, and prisoners locked up without daylight for months.

After a doubling of its prison population in less than a decade, to three times its official capacity, El Salvador now has Latin America’s most overpopulated jails outside Haiti. Life inside is “a journey into hell,” says David Blanchard, a Catholic priest in San Salvador. He describes intolerable heat and damp. The church runs monthly missions to the jails to dispense toothpaste, shampoo and basic food supplies. Last year storms prompted an outbreak of scabies.

The huddled masses

Prison-building rarely keeps up with the expansion of the prison population. In Venezuela, for example, Mr Chávez’s government has built only one new prison in 13 years in power, though it has also expanded Yare, where the president was himself interned after leading a failed military coup in 1992. Built for 1,100 prisoners, Santiago’s San Miguel jail held over 1,900 at the time of the fire. Honduras has about 12,000 prisoners in a system designed for 8,300, says Malcon Guzmán, a Supreme Court official.

The software of the prison system is as defective as its hardware. Budgets for running jails tend to be meagre. In Honduras 97% of the prison budget goes on warders’ salaries and prisoners’ food, leaving very little to keep the prisons in sanitary and safe conditions. Even so, the government spends just 13 lempiras ($0.66) per inmate per day on food, and guards are often poorly paid. In many Latin American countries, prisons are staffed by police officers who do not regard this as a good career move and who are not professionally trained for the task, according to Andrew Coyle of the International Centre for Prison Studies at Essex University in Britain.

There are a couple of other reasons for overcrowding. Torpid justice systems mean that many prisoners are on remand, yet to be convicted of any crime. Prison reformers in Venezuela say around 70% of inmates have yet to be sentenced; many wait years even for a hearing, and must pay gang bosses for the privilege of going to court. Sentenced prisoners, on the other hand, have been known to bribe their way to freedom. Around half of the inmates in both Brazil and Honduras have not been sentenced. Remand prisoners can languish for years, mixing with hardened gang members. The result is that jails are “schools of crime”, says Migdonia Ayestas of the Observatory of Violence, a Honduran NGO.

Some prisons in Brazil are so chaotic that inmates are not released once their sentences are over. Other prisoners, such as Marcos Mariano da Silva, a mechanic arrested for murder in 1976, are victims of mistaken identity. He spent six years in jail in Pernambuco before the real culprit was arrested and he was released. Three years later he was stopped by traffic police who rearrested him as a fugitive. He spent 13 more years in jail, contracting tuberculosis. He died last year, hours after hearing that the state government had lost its appeal against paying him compensation.

The second reason for overcrowding is draconian public and official attitudes to crime. In El Salvador, public support for mano dura (“iron fist”) has filled the jails, mainly with members of youth gangs whose only crime may be sporting a tattoo. Now even temporary holding cells, which have no budget for food, are full. In Brazil judges routinely jail those accused of drug offences, which are exploding in number. In 2005 a tenth of those in prison were there because of drugs offences; now it is a quarter. Most of the prisoners he sees in Paraíba’s jails, says Father João Bosco do Nascimento, one of the prison visitors briefly locked up last month, have committed property or drugs crimes.

Yet, despite all the evidence that Brazilian prisons are hellish and lock up many of the wrong people, there is scant sympathy for those behind bars. In an opinion poll in 2008, 73% said that prison conditions should be made tougher still. Poor and black Brazilians are as likely to be hard-line as rich, white ones are, even though they are far more likely to be put behind bars themselves. In Brazil the prison population is overwhelmingly ill-educated (two-thirds of prisoners did not finish primary school) and poor (95%). Blacks are twice as likely as whites to be in jail (they form two-thirds of prisoners but only half of the population). On the other hand, public-sector workers, politicians, judges, priests and anyone with a degree cannot be held in a common prison while awaiting trial. That is one reason why pressure for prison reform has been so weak.

New model prisons

Nevertheless, there are stirrings of change in Latin America. These have gone furthest in the Dominican Republic, which began to reform its prisons in 2003. Nearly half its 35 jails now run under new rules. These start with the recruitment of civilian staff, who have no ties to the army or police. Recruits go through a year’s training at a college which operates from a garish villa that once belonged to Rafael Trujillo, the country’s notorious former dictator. Prison directors earn up to $1,500 a month and warders around $400, between two and three times the old salaries.

Prisons must be turned into schools to provide inmates with an education, says Roberto Santana, a former university rector who was director of the new prison system until last month. He made learning to read compulsory for prisoners, on pain of losing privileges, such as conjugal phone-calls and visits. At the Najayo women’s prison, where the walls display prisoners’ artwork and trophies won in inter-prison dominoes tournaments, 36 of the 268 inmates are studying for university degrees in law and psychology. Prisoners are out of their cells between 7.30am and 10pm. Some of those not studying work in a bakery. After their release, the new system helps prisoners to find work.

Mr Santana prevented overcrowding by controversially refusing to take prisoners if there is no room for them. He says this dissuades judges and prosecutors from jailing people without good reason. Prison authorities go to great lengths to keep inmates in touch with their families. Najayo prisoners make gifts such as candles and jewellery, which are sold in local markets and the profits divided between the prison, the inmate and her family.

At around $12 per prisoner per day, the new system costs more than twice as much as the old. Not everyone approves of spending cash on criminals, but Mr Santana insists this is “an investment that gives an immense saving to society”. For those in the new system, the reoffending rate within three years of release is less than 3%. Though that implausibly low figure may reflect police incompetence in catching repeat offenders, it compares with about 50% for the old system.

The Dominican Republic has become a model for others to follow, with Honduras and Panama recently seeking advice there. El Salvador, too, has made some progress. It has built new prisons which are among the region’s better ones, says Amado de Andrés, an official at the UN Office on Drugs and Crime. It moved from a written to an oral system of justice in 1998, which speeded up trials and cut the number of remand prisoners. (Mexico is adopting a similar system.) In Honduras Mr Guzmán says that the prison system is shifting its focus to be “not just repressive but preventive”, with more emphasis on education, health and finding jobs. A new law transfers control of jails from the security ministry to the interior ministry, a move supported by the national human-rights commission. New prisons are being built, partly with money seized from drug-traffickers.

Venezuela has promised reform, but not yet accomplished much. The 1999 constitution mandated the employment of professional prison staff. But only a handful of the 1,400 graduates of a pioneering training institute for penitentiary staff have jobs in a system still dominated by the security forces, according to human-rights groups. The institute has now merged with a new police university. After the El Rodeo riot, the government set up a new prisons ministry and says eight new jails will be ready by March 2013.

In Chile, after the San Miguel fire, the conservative government announced a sweeping prison-reform plan, to improve conditions, build four new prisons (at a cost of $410m), recruit 5,000 more prison warders, segregate prisoners by the severity of their offence, and cut prison demand by requiring more offenders to do community service. The aim is to cut overcrowding, from 60% to 15% by 2014. A previous centre-left government turned to the private sector to build and run seven new jails. But the new prisons will be state run.

Seeds of hope

Brazil also has some “small seeds of hope”, says Father do Nascimento: a few enlightened judges are using their power to order community service instead of jail. The National Justice Council, a branch of the judiciary, has examined the cases of 300,000 prisoners in the past two years, freeing 22,600 whom it found should not have been in jail. The federal government’s power to improve prison conditions is limited, says Augusto Rossini, a senior official at the justice ministry: it is judges who pass sentences, and states that run prisons.

But the government is trying to do what it can. The four high-security federal units it has built since 2004 to take gang leaders have helped states to manage their prisons, and cut the number of prison uprisings by 70%, Mr Rossini says. It is building a fifth. In the next two years it will spend 1 billion reais ($500m) on health-care in prisons, and is working on digitising prison records. Last year a federal decree banned pre-trial detention for first-time offenders accused of lesser crimes; Congress has passed a law giving prisoners a day off their sentences for every 12 hours spent studying or working.

A repeat visit to Romeu Gonçalves de Abrantes prison by Paraíba’s council members eight days after they were illegally detained found the prison was cleaner and the inmates decently dressed, and with access to washing facilities. Progress will come from such small victories, as well as wholesale reforms. The sooner the public realises that decent prisons reduce crime, not reward it, the better both for prisoners and for other Latin Americans.