Na aula de Ciência Política do dia 28.10.11, quando estava sendo abordado a questão da governabilidade do sistema presidencialista dos Estados Unidos, foi falado do termo ‘pork barrel’, que aqui no Brasil é denominado de ‘política de São Francisco de Assis: é dando que se recebe’, ou seja, as alianças e acordos, muitos vezes escusos e não republicanos, que o governo precisa fazer com o legislativo para garantir a governabilidade e ter condições políticas de implementar o seu plano de governo.

Na aula de Ciência Política do dia 28.10.11, quando estava sendo abordado a questão da governabilidade do sistema presidencialista dos Estados Unidos, foi falado do termo ‘pork barrel’, que aqui no Brasil é denominado de ‘política de São Francisco de Assis: é dando que se recebe’, ou seja, as alianças e acordos, muitos vezes escusos e não republicanos, que o governo precisa fazer com o legislativo para garantir a governabilidade e ter condições políticas de implementar o seu plano de governo.

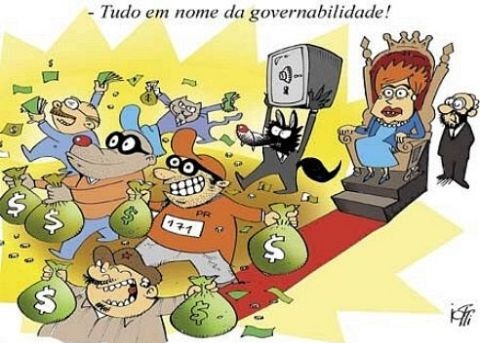

As vezes (em todas elas) achamos um absurdo o fato, por exemplo, do governo da presidente Dilma entregar ministérios inteiros, de ‘porteira fechada’, para um único partido (vide caso recente do Ministério dos Esportes, nas mãos do PC do B – que só possui 11 deputados federais), em nome da chamada ‘governabilidade’, mas, entretanto, todavia… (é difícil admitir isso) considerando o sistema de governo vigente no Brasil, assim como nos Estados Unidos da América (lá em um grau, atualmente, infinitamente menor do ponto de vista da corrupção) esta prática se faz necessária.

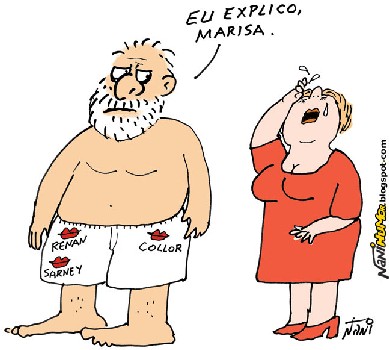

Aqueles governos, em sistemas presidencialistas democráticos, que não se submetem a este tipo de ‘jogo político’, quando possuem minoria no legislativo (quase sempre), estão fadados a uma paralisia total ou ainda (apesar do presidente, nestes sistemas, ser considerado primus solus), serem apeados do governo através de manobras constitucionais válidas e/ou tramas políticas com origem no parlamento (qualquer semelhança com o caso Collor é mera coincidência, ou será mesmo que ele foi impeachmado em função de uma Fiat Elba? ou da força dos estudantes caras pintadas?).

Nos Estados Unidos a prática do chamado ‘pork barrel’ é praticamente institucionalizada, ao ponto da população, a administração (e a imprensa) saberem exatamente a quantia despendida pelo Estado, a cada ano, neste ‘jogo político’. Alguns exemplos beiram o ridículo ou o absurdo (mais ainda do que no Brasil), como o caso, da chamada ‘Bridge to Nowhere’ (ponte que liga nenhum lugar a lugar nenhum), que o governo federal da época construiu, a pedido e sob pressão (para ter o apoio) do senador republicano do estado do Alasca, Ted Stevens, que custou (a ponte e não o senador) mais de 390 milhões de dólares e conecta uma ilha (Revillagigedo) onde vivem 5o moradores ao aeroporto internacional Ketchikan.

Por os Estados Unidos adotar um sistema eleitoral majoritário, para a eleição dos parlamentares, creio que esse ‘jogo político’ se torna mais acentuado, uma vez que para ter apoio de um parlamentar de um determinado distrito, que é do partido de oposição, o governo necessita ‘barganhar’ o seu apoio e o deputado ou senador, para se perpetuar no poder (a eleição para deputados nos EUA ocorre a cada 2 anos) se submete a este tipo de lógica para ‘ad hoc’ apoiar o governo em determinados projetos e garantir o apoio local dos eleitores do seu distrito.

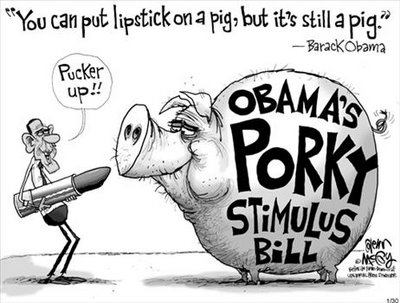

“Early in his presidency, President Obama publicly urged Congress to cut wasteful spending. But by March 2009, Congress had presented him with a $410 billion stimulus bill that included $7.7 billion in pork — and he signed it.” By Casey Scudder

“No início da sua presidência, Obama exortou/convocou o Congresso americano a cortar os gastos considerados supérfluos, quando da elaboração do orçamento anual, entretanto, em março de 2009, o Congresso apresentou um orçamento a Obama de 410 bilhões de dólares (com os chamados ‘estímulos a produção’), que incluía 7,7 bilhões em gorduras ‘políticas’ (pork barrel) — e ele (Obama) o assinou.”

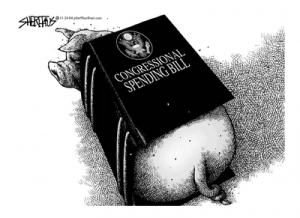

Definição, segundo o Wikipedia, do termo ‘pork barrel’:

History

The term pork barrel politics usually refers to spending that is intended to benefit constituents of a politician in return for their political support, either in the form of campaign contributions or votes. In the popular 1863 story “The Children of the Public”, Edward Everett Hale used the term pork barrel as a homely metaphor for any form of public spending to the citizenry. After the American Civil War, however, the term came to be used in a derogatory sense. The Oxford English Dictionary dates the modern sense of the term from 1873. By the 1870s, references to “pork” were common in Congress, and the term was further popularized by a 1919 article by Chester Collins Maxey in the National Municipal Review, which reported on certain legislative acts known to members of Congress as “pork barrel bills”. He claimed that the phrase originated in a pre-Civil War practice of giving slaves a barrel of salt pork as a reward and requiring them to compete among themselves to get their share of the handout. More generally, a barrel of salt pork was a common larder item in 19th century households, and could be used as a measure of the family’s financial well-being. For example, in his 1845 novel The Chainbearer, James Fenimore Cooper wrote, “I hold a family to be in a desperate way, when the mother can see the bottom of the pork barrel.”

Definition

Typically, “pork” involves funding for government programs whose economic or service benefits are concentrated in a particular area but whose costs are spread among all taxpayers. Public works projects, certain national defense spending projects, and agricultural subsidies are the most commonly cited examples.

Citizens Against Government Waste outlines seven criteria by which spending can be classified as “pork”:

- Requested by only one chamber of Congress;

- Not specifically authorized;

- Not competitively awarded;

- Not requested by the President;

- Greatly exceeds the President’s budget request or the previous year’s funding;

- Not the subject of congressional hearings; or

- Serves only a local or special interest.

Examples

One of the earliest examples of pork barrel politics in the United States was the Bonus Bill of 1817, which was introduced by John C. Calhoun to construct highways linking the Eastern and Southern United States to its Western frontier using the earnings bonus from the Second Bank of the United States. Calhoun argued for it using general welfare and post roads clauses of the United States Constitution. Although he approved of the economic development goal, President James Madison vetoed the bill as unconstitutional.

One of the earliest examples of pork barrel politics in the United States was the Bonus Bill of 1817, which was introduced by John C. Calhoun to construct highways linking the Eastern and Southern United States to its Western frontier using the earnings bonus from the Second Bank of the United States. Calhoun argued for it using general welfare and post roads clauses of the United States Constitution. Although he approved of the economic development goal, President James Madison vetoed the bill as unconstitutional.

1873 Defiance (Ohio) Democrat 13 Sept. 1/8: “Recollecting their many previous visits to the public pork-barrel,… this hue-and-cry over the salary grab… puzzles quite as much as it alarms them.”

1896 Overland Monthly Sept. 370/2: “Another illustration represents Mr. Ford in the act of hooking out a chunk of River and Harbor Pork out of a Congressional Pork Barrel valued at two hundred and fifty thousand dollars.”

One of the most famous alleged pork-barrel projects was the Big Dig in Boston, Massachusetts. The Big Dig was a project to take an existing 3.5-mile (5.6 km) interstate highway and relocate it underground. It ended up costing US$14.6 billion, or over US$4 billion per mile. Tip O’Neill (D-Mass), after whom one of the Big Dig tunnels was named, pushed to have the Big Dig funded by the federal government while he was the Speaker of the United States House of Representatives.

Pork-barrel projects, or earmarks, are added to the federal budget by members of the appropriation committees of United States Congress. This allows delivery of federal funds to the local district or state of the appropriation committee member, often accommodating major campaign contributors. To a certain extent, a member of Congress is judged by their ability to deliver funds to their constituents. The Chairman and the ranking member of the U.S. Senate Committee on Appropriations are in a position to deliver significant benefits to their states.

Pingback: Aula 24 – Ciência Política – 28.10.11 | Projeto Pasárgada

Pingback: O futuro: O Brasil estragou tudo? – The Economist – setembro/2013 | Projeto Pasárgada